As we look at discrimination in human rights legislation, we finally learn why Jérémy Gabriel’s complaint would not meet the standard anywhere else in Canada.

Human Rights Legislation

Long before the Charter, all provinces, as well as the federal government, had established human rights commissions and tribunals (the territories followed later). While there are some differences, the legislation from one province or territory to another remains very similar. Quebec, notwithstanding its many similarities, has one significant exception, so we will discuss this province separately.

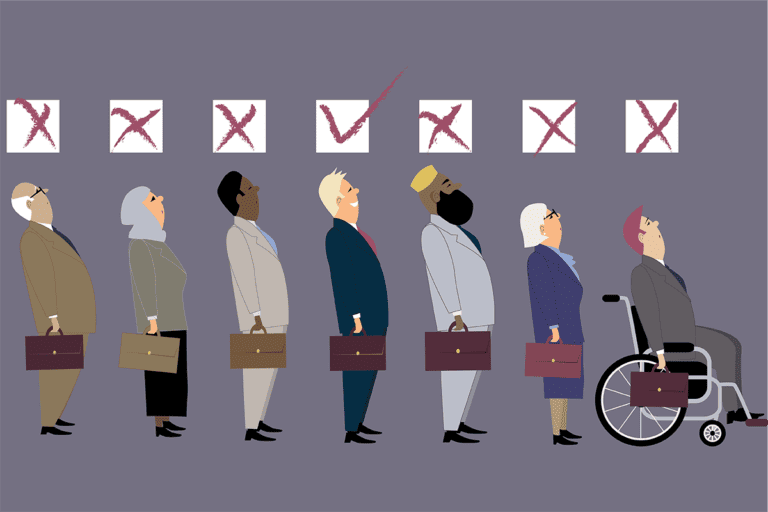

Human rights legislation focuses on discrimination and harassment, including sexual harassment. The Code or Act supersedes other legislation, and is subject only to the Charter. As with the Charter, federal, provincial, or territorial human rights legislation outlines specific identity characteristics, known as protected grounds, prohibited grounds, or applicable characteristics (link is a .pdf download).

Protected Grounds

All jurisdictions protect:

- age

- race

- colour

- physical or mental disability

- sex, including pregnancy and sexual harassment

- sexual orientation

- gender identity

- place of origin or nationality

- marital status

- family status

- religion or creed

Most include:

- source of income or receipt of public assistance

- ethnic or linguistic background or origin

- ancestry

- political beliefs

- pay equity

A number of other grounds are specific to some jurisdictions; search online for the specifics of the Code or Act you are interested in.

Protected Areas

Not only are there protected grounds, but there are also protected areas. Generally, they include:

- employment

- access to goods, services, and public facilities

- housing

- membership in trade unions

- contracts

- leasing or sale of property

Many include displayed notices and publications.

Discrimination

Discrimination is an action, speech, or behaviour, based on a protected ground, that leads to unfavourable treatment of another individual or group. It may produce hatred, intolerance, or prejudice, and can be either overt or covert. In both cases, it is intended; in the former it is “in your face”, while in the latter it is masked.

Discrimination can also be systemic: policies and practices that seem neutral on the surface, but in practice are not. Systemic discrimination is unintentional and will be discussed in an upcoming article.

Harassment

Harassment is one way of acting out discrimination. It is a comment or behaviour that is unwelcome, or ought to be known to be unwelcome. Once again, we come face-to-face with the reasonable person standard. Harassment must be based on a protected ground, and must take place within a protected area. It can be caused by anyone, whether that person is in a position of authority, or is a powerless peer. Although generally an ongoing behaviour, one harassing incident may be enough.

To determine if you are being harassed or discriminated against under the law, you must first show that the negative behaviour was based on a protected ground—for example, disability. You must next show that the comments or actions took place within a protected area—for example, school, workplace, or an attempt to access services or rent an apartment.

Intent Does Not Matter

There is one critical area where the Ward majority got it wrong: Under discrimination law, no matter where you are in Canada, “but I didn’t mean to” or “it was just a joke” is not an excuse. Citing the 1985 case that set the standard (Ontario Human Rights Commission v. Simpsons-Sears Ltd), the dissenting justices reiterated:

[150] … it is immaterial whether Mr. Ward intended to mock Mr. Gabriel because he has a disability, whether Mr. Ward was joking or being serious, or whether Mr. Gabriel was skewered in the same way as other celebrities. The issue is not Mr. Ward’s stated intention not to discriminate against Mr. Gabriel. The issue is the impact of Mr. Ward’s comments on this child with a disability. [italics in original]

Saying “this child” leads us to another point: Discrimination or harassment is based on the impact on the person or group who filed the complaint. It does not matter if another person with a disability found the jokes funny. It does not matter if you are the only member of your identity group being targeted. You do not have to show evidence that it is happening to others. It is still discrimination against you, even if it is only against you.

Filing A Complaint

When it comes to filing a human rights complaint, it takes more than just pointing a finger at somebody. You must write out, in detail, what happened and when it occurred:

- if there are witnesses, you need to list them

- if there are documents, you need to provide them

The tribunal and courts understand that discrimination and harassment often occur in private—an “I said, they said” situation, so you do not need absolute proof. But in the absence of witnesses or documentation, your story must be as detailed as possible. The tribunal member will then decide which of your stories is more likely than not to be true.

Poisoned Environment

You do not necessarily need to be the direct target of discriminatory behaviour to file a complaint. Poisoned environmentis the term used when the unequal treatment of a person or group, resulting in unequal conditions, interferes with your performance or causes you emotional stress not experienced by others.

The Directing Mind

Finally, there is something called the directing mind, which includes people with decision-making authority or significant responsibility over others.

If a person or group files a human rights complaint against a company, they could also specifically name an authority figure who either knew of the comments or behaviour and did not take reasonable steps to stop it, or were doing the discriminating or harassing themselves. In such instances, a tribunal or court could find the individuals personally responsible for some of the awarded compensation. Calego , the case central to discussions in Ward, is a 2013 Quebec Court of Appeal decision that provides a good example of this concept.

Calego International Inc: The Discrimination

On July 11, 2006, Stephen Rapps, President of Calego International Inc, was informed of the dirty state of the common kitchen and bathrooms in the warehouse. It turned out that the facilities were dirty because there were too many employees for the space.

But without investigating, Rapps told Vincent Agostino to gather all forty Chinese employees for an impromptu meeting; the remaining twenty employees of diverse backgrounds were exempt. Agostino was the owner of Agence Vincent, the employment agency that recruited, hired, and paid the employees. He worked on site ninety percent of the time.

Making sure an interpreter was available to translate his words from English to Mandarin, Rapps said, in part:

The employees were shocked. Some spoke back, and Rapps threatened to kill one who told him to “f@#k off.” Agostino told the employees to leave. He had not tried to intervene or stop Rapps; in fact, he had even laughed. And it was Agostino who posted a sign regarding cleanliness, in Mandarin only, in the bathroom.

The employees willingly returned the next day after being told President Stephen Rapps would apologize, but he never showed. Representing the company in his place were his father and cousin, neither of whom apologized.

As the meeting came to an end, one employee handed the cousin a list of four things the employees wanted: “A written apology, a clean working environment, particularly in the kitchen, the designation of regular supervisors, compensation.”

The company agreed to improved conditions and regular supervisors, and were willing to pay a full day’s wage even though the employees only worked the half-day. Stephen Rapps was prepared to offer a verbal apology but, “no way” would he put it in writing.

The Human Rights Complaint

Ultimately, fifteen employees filed a human rights complaint against the two companies, Calego and Agence Vincent, specifically naming Stephen Rapps and Vincent Agostino. The Human Rights Tribunal found each company (with their respective leader) equally responsible for $7,000 in moral damages, and $,3000 in punitive damages, per appellant.

The defendants appealed both the finding of discrimination, and the amounts and division of the settlement.

The Appeals Court held that discrimination had occurred, but:

- Removed the punitive damages.

- Found Calego and its president, Stephen Rapps, seventy-five percent responsible for the moral damages, because he had made the derogatory comments.

- Held Vincent Agostino and his company responsible for twenty-five percent of the damages. Even though he was the owner of a separate company, he was seen as a boss over the employees, and he had failed to intervene.

Back to Jérémy Gabriel's Complaint

And so you have it: Within the parameters of all other human rights codes across Canada, Mike Ward’s skits and online posts were not discriminatory against Jérémy Gabriel. While Jérémy could argue that the ground was disability, he could not link it to a protected area. After all, Mike Ward did not enter the school and tell his jokes.

However, if kids, while at school, were telling the jokes, Jérémy and his parents could have filed a complaint against the school board. They could even have gone so far as to list the principal or specific teachers, if these authority figures knew of the harassment and did not take reasonable steps to stop it.

Schools are Legally Bound To Intervene

While recognizing that schools are rampant with negative behaviours, school boards and schools are expected to have and enforce, to the best of their ability, anti-harassment and anti-discrimination policies. And when they know of specific issues, they are legally bound to intervene in a reasonable manner.

Most schools have anti-bullying policies. Bullying goes beyond the limitations of protected grounds. School administrators, teachers, and staff are asked to intervene, regardless of the reason for the bullying, but unlike human rights violations, their failure to do so does not (usually) make school boards legally responsible.

The Quebec Difference

So what makes Quebec so different? Why did the Human Rights Commission, tribunal, appellate court, and four of the nine SCC judges all believe there was discrimination under the law? It all comes down to the Quebec Charter.