Canadian law includes court decisions, legislation, and the Canadian Constitution. When and how did Canadians bring the Constitution home?

We have looked at court decisions, and followed Jérémy Gabriel and Mike Ward’s case from a human rights commission to the Supreme Court. As we build an understanding of discrimination, here’s a glimpse at government legislation, and the Canadian Constitution.

Government Legislation

The second area of Canadian law is federal and provincial legislation. However, because of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which falls within the Canadian Constitution, we have little reason to discuss how legislation is created in a discussion of discrimination.

Briefly, elected members of Parliament (federal government) and provincial legislatures introduce and debate bills. A majority vote, including both the House of Commons and the Senate in federal instances, turns the bill into law … almost.

While no longer a colony of Britain, Canada is still associated with the monarchy. The monarch’s federal representative is the Governor General; in each province, it is the Lieutenant Governor. It is their responsibility to rubber stamp the bill, thus giving it “royal assent” as the final step.

The Canadian Constitution

The British North America Act

This brings us to the third area, the Constitution. In July 1867, Canada went from being a colony of Britain to becoming its own country. To achieve this, the British North America Act (BNA), which set out the responsibilities of government, was drafted. It “was a practical contract, drawn up behind closed doors by a few dozen colonial politicians and imperial officials.” Yet while we may have been our own country, we were still bound by many British laws. Gradually, this changed:

“Over time, British laws—with the one all-important exception of the BNA Act—ceased to apply in Canada after the Statute of Westminster in 1931. A distinct Canadian citizenship was established in 1947, and in 1949 the Supreme Court of Canada replaced the London-based Judicial Committee of the Privy Council as the ultimate court of appeal.

Unlike Australia or South Africa, however, Canada was unable to take complete control of its own constitution … primarily because there was no agreement on how it should be amended afterwards.”

Bringing The Constitution Home

In November, 1981, after much drama and power politics, Canada’s federal government, and nine of ten provincial politicians (the government of Quebec did not sign on), finally found agreement among compromise. And on April 17, 1982, with Queen Elizabeth of England and Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau of Canada taking centre stage, the Constitution Act, 1982 came into existence.

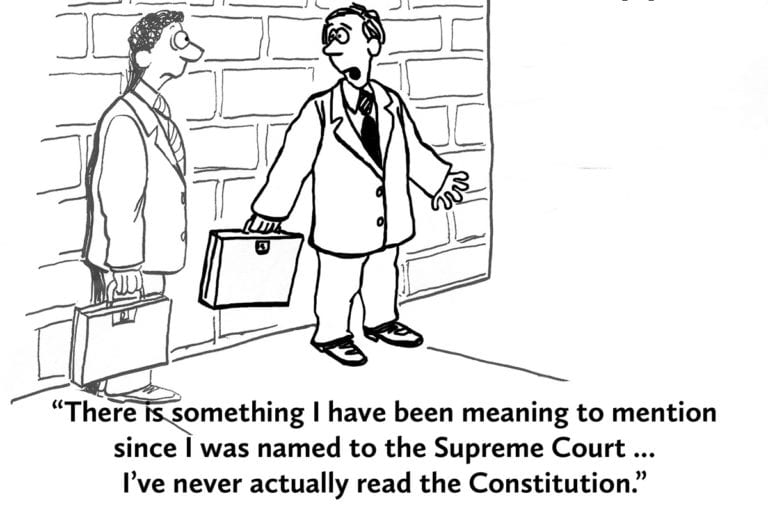

The Constitution Act, 1982 sets out the basic rules for Canada as a country. Among other things, it defines the powers held by the federal government, and for each province or territory. Written directly into the Constitution is the declaration that it is the highest law in Canada; all other laws must be consistent with it. In other words, the prime minister and the provincial premiers gave the courts, not themselves, the last word (link is a .pdf download):

“The wider power of the courts to strike down and rework legislation has generated controversy but when politicians complain about ‘judicial activism,’ journalists should bear in mind that it was elected politicians, not unelected judges, who thrust this responsibility upon the courts.”