The Skeleton Argument is a bare-bones presentation of your case. But if changing the conversations is the goal, you might be asking: “Why use law metaphors?”

Skeletons, Laws, and Legal Systems

Laws have told women, Indigenous peoples, and Black people alike that we were not persons, but the property of fathers, husbands, and white men. Legal systems are ripe with stagnation and very slow to change, and have explicitly built in many discriminatory practices, past and present.

Judges would no doubt argue that their decisions are always fact-based and neutral. History shows otherwise. Rightness and wrongness are based on the morals and emotions-based biases of their era, making you as much a part of “the system” as any judge. Put simply, laws don’t change until a critical mass of opinions change.

Changing the conversations requires transforming emotions and alerting yourself to biases that negatively influence your beliefs and decisions—emotions and biases you may not even realize you have. Metaphor is your window to these emotions. When it comes to biases, prejudices, and systemic discrimination, a common metaphor is the court of public opinion (CPO). By using a courtroom backdrop in this book, I can put you as the juror, reminding you that there is no such thing as an innocent bystander. You have emotions, biases, and opinions. You make decisions, and you impact others.

In law, The Skeleton is a succinct outline, or bare-bones presentation of your case, submitted to the judge in advance of the trial. The skeleton, of course, is a metaphor—a tool you naturally use as you unwittingly describe your emotions about a situation. Since your metaphors represent your emotions, transforming your metaphors can quickly bring positive change and more accurate decision-making. The skeleton metaphor is a case in point.

A Closer Look at The Skeleton

When you think of law while picturing the skeleton, what scene comes to mind? Is it something archaic, cobwebbed, old-fashioned, and decrepit, as in the chapter image? Can you smell the mould in the walls? Do you want to sneeze from the dust in the air? Are you quickly brushing off your skin, thinking the slightest breeze is a spider crawling up your arm? Do you fear wolves hidden in the fog outside the window, howling at the moon? The accompanying suggestion to this scene might be that laws hold you back, exhaust you, fail you, or have not adjusted to the times.

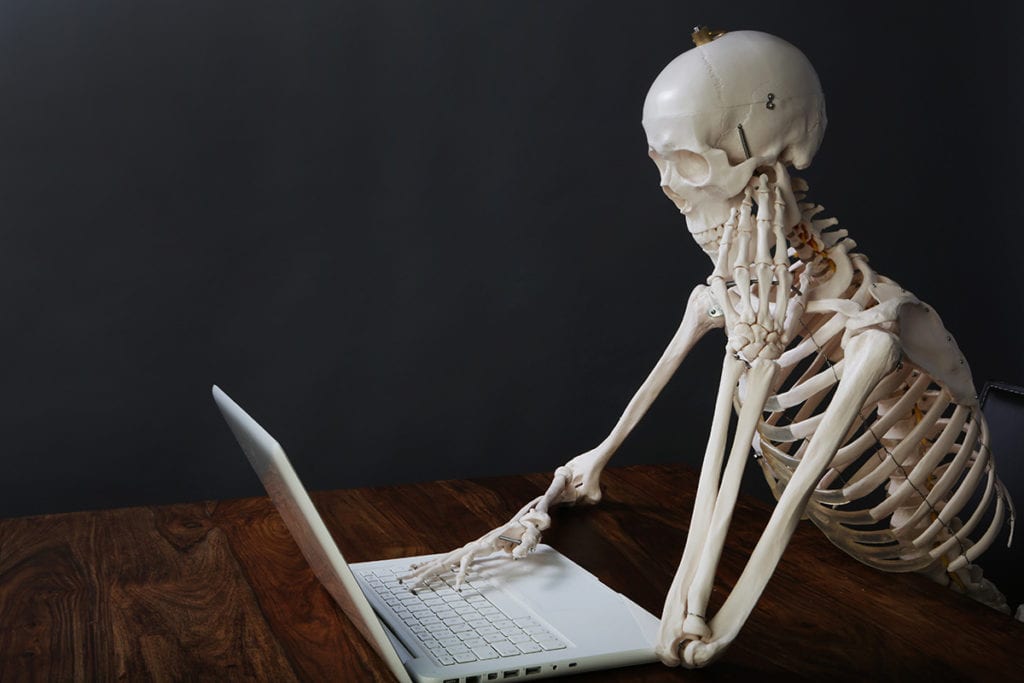

But what if your scene is more modern, like this healthy and alert skeleton, using a laptop?

Clean walls, a clutter-free table, and a relaxed but focused body position actively researching reflect an optimism or positive outlook. This scene might suggest you find the law effective, helpful, and applicable to modern life.

The sights, smells, tastes, textures, and sounds of your scene—that is, the details of your personalized impression of the skeleton metaphor:

- Reflect your emotions.

- Frame your conversations and recommendations.

At the very least, before making a decision, you should have a sense of the emotions your metaphors conjure up; ideally, you will also transform your metaphors—and therefore your negative emotions. From this clean slate, you can take your best next step. Not necessarily your last step, but your best step.

Going Forward

While the fact-based Skeleton Argument lets the judge know what to expect in advance of the trial, jurors will receive this information through a more storied opening statement. Still factual, the opening statement is intended to pull on your emotions and draw you into the story.

Next, I deliver my opening statement to you, the juror in this CPO. From this point forward, I challenge you to better describe your own scene as you read the various events and stories. Pay attention to the metaphors I use and the emotions I am trying to elicit. If you accept the challenge, changing the conversations will naturally follow.